EXPOSICIONES

Barrios. Madrid 1976-1980

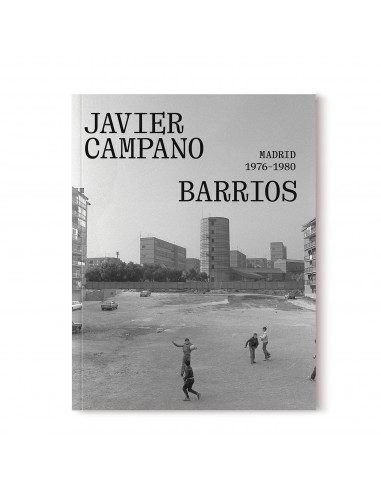

Javier Campano

11 jun. — 8 sep. 2024

El Águila

— Madrid

Inauguración

11 de junio, 12h

Comisariado por

Ana Berruguete

Organiza

Comunidad de Madrid. Consejería de Cultura, Turismo y Deporte. Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural y Oficina del Español

Horarios de la sede

Martes a sábado

10:00 – 14:00 y 16:00 - 20:00

Domingos y festivos

10:00 – 14:00

Cerrado lunes de julio y agosto

Sede

El Águila

Sala Cristóbal Portillo

Ramírez de Prado, 3

Mapa

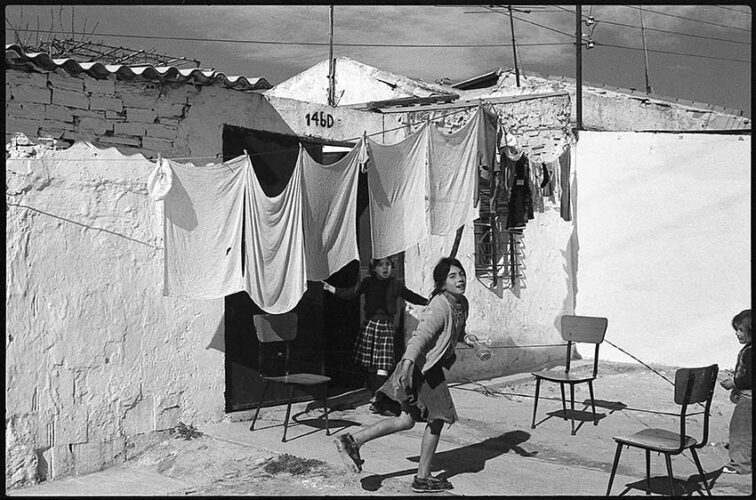

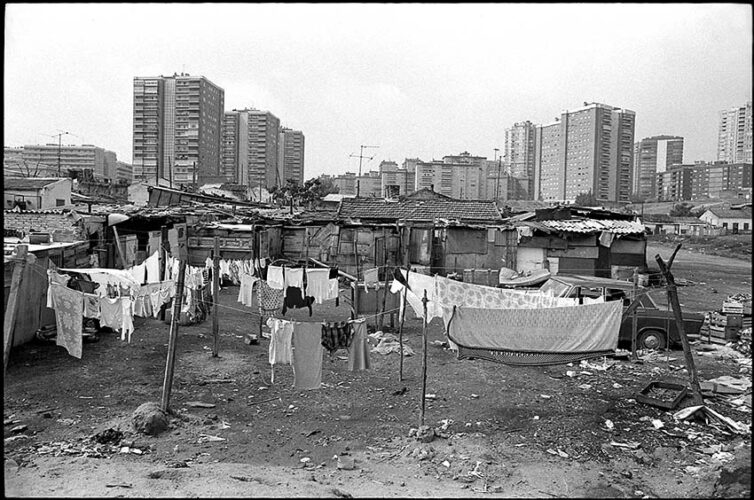

A través de su lente, y con la agudeza y elegancia visual que le caracterizan, el fotógrafo Javier Campano (Madrid, 1950) supo documentar la plena transformación a finales de los años 70 de un Madrid ilusionante, -e ilusorio también-, con grandes problemas urbanísticos y de vivienda aún por resolver para una población en aumento, procedente en las décadas anteriores, de las zonas rurales. La ciudad se debatía en muchos de sus barrios, entre grandes bloques de ladrillo y multitud de infraviviendas o casas bajas habitualmente autoconstruidas, sin agua ni alcantarillado, cuyos habitantes aspiraban a vivir en esos nuevos pisos que no podían pagar.

Como un “ojo móvil”, el fotógrafo deambuló entre los habitantes sin ser visto. Había ocasiones en las que un autobús le acercaba a barrios alejados del centro como Orcasitas o Vallecas, pero también a Chamartín o el Barrio del Pilar. Otras, paseaba sin rumbo fijo, y podía empezar a andar en Cascorro y acabar en Legazpi o empezar en Goya y acabar en Ciudad Lineal.

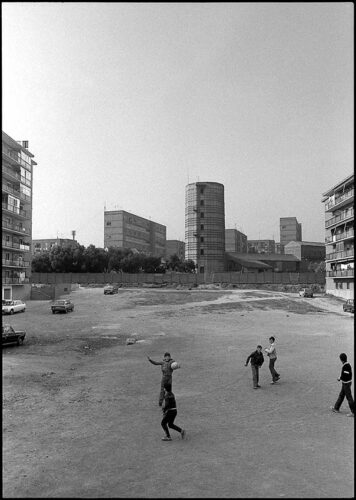

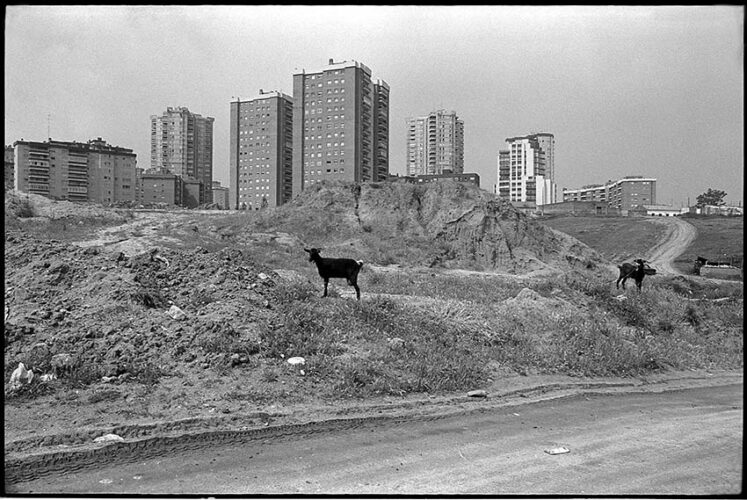

Los barrios, sus rincones y habitantes cobraban una nueva dimensión, sumergidos en una atmósfera de blanco y negro que él mismo definió como “irreal y poética”. Los niños que jugaban en improvisadas canchas de fútbol en solares, daban cierta humanidad. El barro, los huertos y los burros: iconografías rurales que competían con la enorme presencia de bloques de reiterado ladrillo rojo. La gente era receptiva a dejarse fotografiar. Pensaban que era bueno que se fijaran en ellos y en que se dieran a conocer sus condiciones de vida precarias. En la UVA de Hortaleza o en Orcasitas le abrieron sus viviendas. En Usera, Vallecas o Lavapiés, le hicieron testigo de sus luchas vecinales. Un archivo impresionante que hoy sigue latente. Orgullo de barrio y nostalgia de una historia compartida.

Through his lens, and with the acuity and visual elegance that are his hallmarks, the photographer Javier Campano (Madrid, 1950) managed to document the complete transformation of an exciting—and illusory—Madrid in the late 1970s that had major unresolved urban design and housing problems for an increasing population that had flocked there from the rural areas in the preceding decades. The city was at odds with itself in many neighbourhoods: huge brick apartment buildings along with a plethora of tenements or often self-built houses without either water or sewage, whose inhabitants aspired to live in these new flats they could not afford.

Like a ‘roving eye’, the photographer walked amidst the inhabitants without being seen. Sometimes the bus took him to neighbourhoods far from the city centre, like Orcasitas and Vallecas, but it also took him to Chamartín and Barrio del Pilar. Other times he walked aimlessly; in fact, he might start walking in Plaza del Cascorro and end up in Plaza de Legazpi, or begin in Calle Goya and end up in the Ciudad Lineal district.

Its neighbourhoods, corners and inhabitants took on a new dimension, immersed in a black-and-white atmosphere that the photographer himself defined as ‘unreal and poetic’. Mud, vegetable patches and mules were the rural iconographies that competed with the rows of enormous brick apartment buildings. People were receptive to being photographed. They thought it was good that attention was focused on them and that their precarious living conditions would be shared. It is an impressive archive that is still alive today, neighbourhood pride and nostalgia in a shared story.